A $90 Wrecking Yard Special Turned into a 365hp Small-block Chevy

The small-block Chevy has enjoyed a long, happy life. Sure, the current LS1/LS6 version is quite far removed from the original, but thousands upon thousands of little mouse motors continue to provide the sole means of motivation to everything from stationary irrigation pumps to Le Mans-winning C5R Corvettes. Naturally, this list also includes all manner of boulevard bruisers, street stompers and resto rockets. Heck, we’ve even seen little Chevys under the hood of “Brand X” machinery. The continued popularity of the small-block Chevy is not surprising. Take a look at the combination of power potential and parts availability and multiply that by the cost quotient, and you have the makings of a real success story. Add to this equation the millions of project motors just sitting around junkyards throughout the world, and it is easy to see why enthusiasts continue to embrace the mighty mouse motor as the performance powerplant of choice.

True enthusiasts, especially those raised on performance during the heyday of the muscle-car era, may have taken a look at the title and immediately thought of the L76 365hp 327. An excellent choice of a small block to be sure; but alas, this is not an article on how to restore your L76. The powerplant depicted here would, however, be an excellent replacement for L76 Corvette owners not wanting to rack up the miles on their restored small block. In fact, the 365hp small block detailed here would likely be a significant step up in performance, thanks to the broader torque curve. Let’s not forget the crazy gross versus net and generally inaccurate power ratings offered by the manufacturers back in the ’60s and ’70s. The reality is that the 365hp L76 probably never put out that kind of net horsepower, but this combination comes with nothing less than dyno verification of the performance potential. Unlike the high-strung performers of yesteryear, the elevated power offered by this mild-mannered combination comes with no penalty in idle quality, driveability or the need to run over to the local airport for a few gallons of aviation fuel to achieve maximum performance.

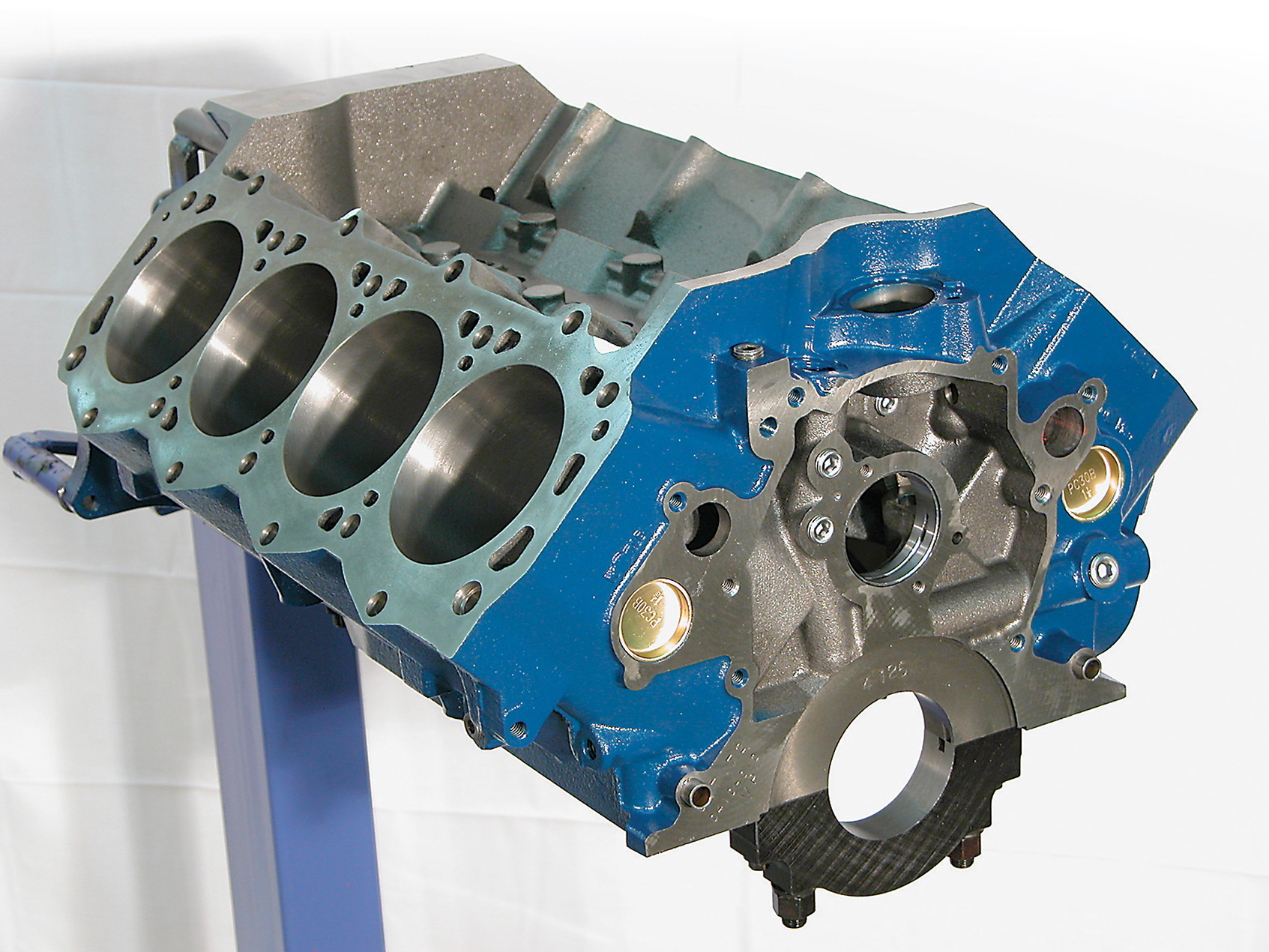

As with most rebuild stories, our 365hp engine started out life as something much less extraordinary. The 350 slated for performance duty was found rusting away in a local wrecking yard. The early ’70s 1/2-ton pickup was well past its prime, but lurking within was a diamond in the rough. Purchased for a mere $90 (a wrecking yard special), the complete used engine turned out to offer the more desirable four-bolt main block, though a two-bolt block would certainly suffice for this particular buildup. The high-mileage motor was disassembled and found to be in good shape. Hardly exotic or even desirable by enthusiast standards, the 882 (a common SBC smog-era casting number) heads featured both small valves (1.94/1.50) and large 76cc combustion chambers. The heads showed all the classic signs of high mileage, but we were not concerned since they would be subjected to a complete rebuild (including larger stainless steel valves in addition to the performance porting). Upon final disassembly, we were pleasantly surprised to see the rod and bearings (and therefore the stock cast crank) in decent shape, and the cylinder walls were free of major scuffing. It looked like we had a good rebuild candidate for our 365hp buildup. The first step in the performance rebuild was to produce a solid foundation, or short block. Our four-bolt 350 was taken to Advanced Machine in Huntington Beach, California, for the necessary machine work. The block was bored and honed to accept a set of .030-over TRW forged replacement pistons. The flat-top pistons featured valve reliefs to accept cams up to .525 lift, or more than we planned for this adventure. The piston design worked with our 75cc chamber heads (milled the deck surface slightly) to produce a pump-gas-friendly static compression ratio of 9.1:1. Note that this was a far cry from the 11.0:1-plus compression ratios run on the original 365hp motors. Advanced Machine also took the liberty of hot-tanking the block and installing new cam bearings. To our surprise, the cast crank was still standard and was in excellent shape. We took the liberty of micro polishing the crank just to make ourselves feel better, but it was actually good to go as it came from the wrecking yard. The forged pistons were used in conjunction with a set of used LT1 pink rods that Advanced Machine had lying around. We could have saved a few bucks by polishing and reusing the stock rods, but we liked having the pink-rod ammo for future bench-racing sessions. The aftermarket is also full of relatively inexpensive forged rods, but our sub-6000-rpm motor required no such hardware. We did pop for a new harmonic balancer, as the high-mileage unit looked ready to give up the ghost at any moment.

With our short block assembled, it was time to turn our attention to the power portion of the buildup. While a quality short block is important, the cylinder heads, cam and induction system are really the determining factors in terms of eventual power output. How do we know? Some time ago we ran a similar small block with a variety of different heads, cams and intakes. Starting at just 229 horsepower, we eventually coaxed well over 500 using the same short block. We had no such wild plans for this little Chevy, as high-dollar aluminum heads, roller cams and racy tunnel-ram intakes were considered unnecessary to reach our goal of 365 horsepower. First on the list was a suitable camshaft. Since this motor was intended for daily street use, we wanted to avoid any radical cam grinds. The original 365hp 327 cam is a perfect example of a wild street cam. Chevy put a ton of duration in its factory performance cams, something that inevitably hurt driveability. We erred on the conservative side in terms of cam profile, choosing a very mild PowerMax hydraulic flat-tappet cam from Crane Cams. The dual-pattern, emissions-legal small-block cam offered a .427/.454 lift split and a 204/216-degree duration (at .050) split, all ground on a 110-degree lobe separation angle. Crane also supplied the necessary hydraulic lifters. Again, note that the mild hydraulic flat-tappet cam was a far cry from the solid flat-tappet cam run in the original 327. The flat-tappet cam made valve adjustment a set-it-and-forget-it proposition.

Next on the to-do list was the cylinder heads. Though a number of great cylinder heads exist for the little Chevy, we opted to retain the stock castings. Producing 365 horsepower using a set of aftermarket heads would be a walk in the park, but doing so with the stock (albeit ported) hardware was much more impressive, not to mention cost effective. Our 882 heads were taken to Competition Heads in Fullerton, California, for porting before being delivered back to Advanced Machine for installation of the larger 2.02 and 1.60 stainless steel valves (from S.I.). The porting and installation of the larger S.I. valves freed up an additional 30-35cfm per runner. The extra head flow allowed our small block to take full advantage of the extra lift offered by the Crane cam. Naturally, the 882 heads received a suitable valvespring package to work with the revised cam specs. The stock springs were long since worn and inadequate even when new. Advanced Machine also set up the heads to accept screw-in rocker studs and guide plates. The change allowed use of a set of Crane 1.5-ratio roller rockers. Sure, we could have retained the stock stamped steel rockers, but we knew the motor would now rev higher than in stock trim and wanted the extra insurance (and valvetrain stability) offered by the roller rockers.

With our long block basically finished, the 350 was missing only the induction, exhaust and ignition system. When it comes to street motors, forget all about the trick single-plane intakes. If you want a broad, usable torque curve with plenty of top-end power, stick to a good dual-plane intake. For our 365hp 350, we chose an Edelbrock Performer RPM Air Gap intake. The RPM version offered superior flow compared to a traditional Performer, while the air-gap feature allowed for airflow to help cool the individual runners. This cooling feature is even more important once the motor is installed in a vehicle. The RPM intake was topped off with a model 4150 Holley 650cfm vacuum-secondary carburetor. A similar-size Holley Street Avenger or even a big Q-jet (or Edelbrock equivalent) would likely work just as well on this SBC combination. Knowing that what goes into a motor must also eventually come out, we equipped the small block with a set of 1-5/8-inch FlowTech headers. The headers were run into a 2.5-inch dyno exhaust featuring Flowmaster mufflers. Naturally a full-length exhaust system may rob the motor of a few horses; so, too, will the installation of the accessories and water pump. Our dyno session included a CSI electric pump, no accessories and the MSD distributor set to provide 35 degrees of total advance. The ported iron heads seemed to run best at 35 degrees, something we attribute to the combustion chamber polishing performed as part of the porting.

While we were anxious to find out if the combination produced the desired results, we curbed our impatience and allowed the motor a good 40-minute break-in period. After a few short whacks to verify the air/fuel curve, we let the hammer fly and were rewarded with peak readings of 364 hp and a whopping 422 lb-ft of torque. The peak power occurred at just 5200 rpm, a fact that should help ensure a long life. The low peak-power rpm also produced an impressive torque curve. Not only did the motor produce 422 lb-ft at 3900 rpm, but the .030-over 350 produced more than 400 lb-ft for nearly a 2000-rpm spread. The motor just missed the 400 lb-ft mark way down at 2500 rpm. It is torque like this that will allow this 365hp version to motor past the high-winding L76 327s of yesteryear. Given the mild cam, ported stock heads and minimal compression, we were quite pleased with both the peak output and the overall power curve. That the motor made peak power at only 5200 rpm indicates that we had plenty of power potential left should we elect to run a wilder cam profile or, better yet, a set of aftermarket cylinder heads. Is the buildup of a 365hp small block that thumps out 422 lb-ft of torque earth-shattering? Probably not, but besting the small-block legends of yesteryear using ported stock heads, a mild cam and 9.1:1 compression should be considered, at the very least, mildly amusing.

Power Graph 365hp Small Block

Power Graph 365hp Small Block

The one thing you should notice even before the impressive peak power number is the broad torque curve. Naturally all the bench-racing centers on the 365 horsepower, but the fact is that it will be the 400-plus lb-ft produced from 2900-4700 rpm that will provide the most smiles per mile. Heck, even down as low as 2400 rpm the small block belted out 390 lb-ft of torque. It is this kind of torque production that will provide crisp throttle response, infinite passing power and the ability to literally shred the hides off most any street tire. The impressive thing about the small block is that this power was produced with a set of ported stock iron cylinder heads; a mild, emissions-legal cam, and pump-gas-friendly compression. If cared for with regular oil changes and tuneups, this motor should provide years and years of trouble-free performance. As a side note, it would also make one heck of a street-driven replacement for that valuable original L76.

Spec Sheet 365hp 355

Spec Sheet 365hp 355

Block: Four-bolt Chevy

Crank: Cast 3.48-inch stroke

Rods: LT1 pink 5.7 inches

Pistons: TRW flat-top replacement single-eyebrow (9.1:1)

Bore Size: 4.030 (.030 over)

Compression Ratio: 9.1:1 with 76cc chamber

Heads: Chevy iron 882 casting, hand ported by Competition Heads

Intake Valve Size: 2.02 (originally 1.94)

Exhaust Valve Size: 1.60 (originally 1.50)

Cam: Crane Cams PowerMax

Lift: .427 in., .454 ex.

Duration (@.050): 204 in., 216 ex.

Lobe Separation: 110 degrees

Intake Manifold: Edelbrock PerformerRPM Air Gap

Carburetor: Holley 4150 650 vacuum secondary

Distributor: MSD billet

Headers: FlowTech 1-5/8-inch

Exhaust: 2.5-inch (dyno)

Mufflers: Flowmaster