Trucks

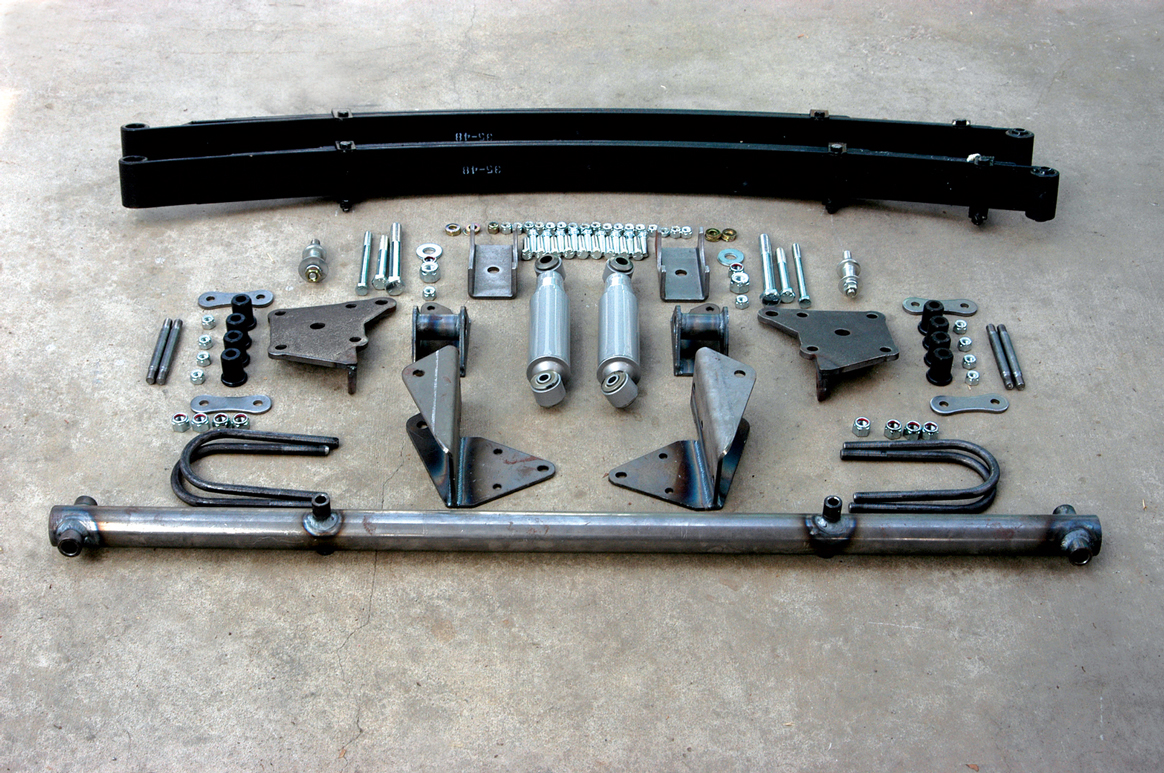

Tall lift kits used to mean a rough ride. Times have changed—the suspension aftermarket has figured out how to accommodate huge meats without inflicting permanent kidney damage on the driver and passengers. Computer-modeling and other engineering advancements prioritize ride quality into the suspension design. Spring packs with more, thinner leafs is an example of how tall-truck suspension philosophy has evolved.

The Helms Bakery Company started delivering bakery goods door to door in 1932 and had a small fleet of trucks servicing the Los Angeles area. The company was very successful, and by the ’50s it had a large fleet of Chevy panel trucks delivering to Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley. The fleet consisted of early ’50s Chevy panel trucks that were modified inside with wood and glass cabinets to store bread and other bakery products. When the trucks were purchased they were ordered with heavy-duty springs that worked well with the heavy wood cabinets installed inside. The company upgraded the fleet as needed, so there were plenty of ’50s Chevy panel trucks that were retired in favor of new trucks in the ’60s. The company eventually succumbed to changing lifestyles in California and closed its doors in 1969.

Dean Brown was looking for another street rod to build after selling his ’40 pickup truck when he heard about a ’52 Chevy panel delivery for sale. As he’d always been fond of these trucks, he decided to take a look. When he saw the panel delivery he found that it was in reasonable condition and was still running fine with the original six-cylinder engine. The truck’s history showed that it was a Helms Bakery truck in the ’50s and had never been modified.

In past stories we have shown you how to shave door handles, install custom outside door handles, round door corners, build suicide doors, add bear claw latches and so on. Now we’re going to offer you a personal favorite custom touch—installing a dash from a ’59-’60 Chevrolet Impala into a ’56 Ford F-100.

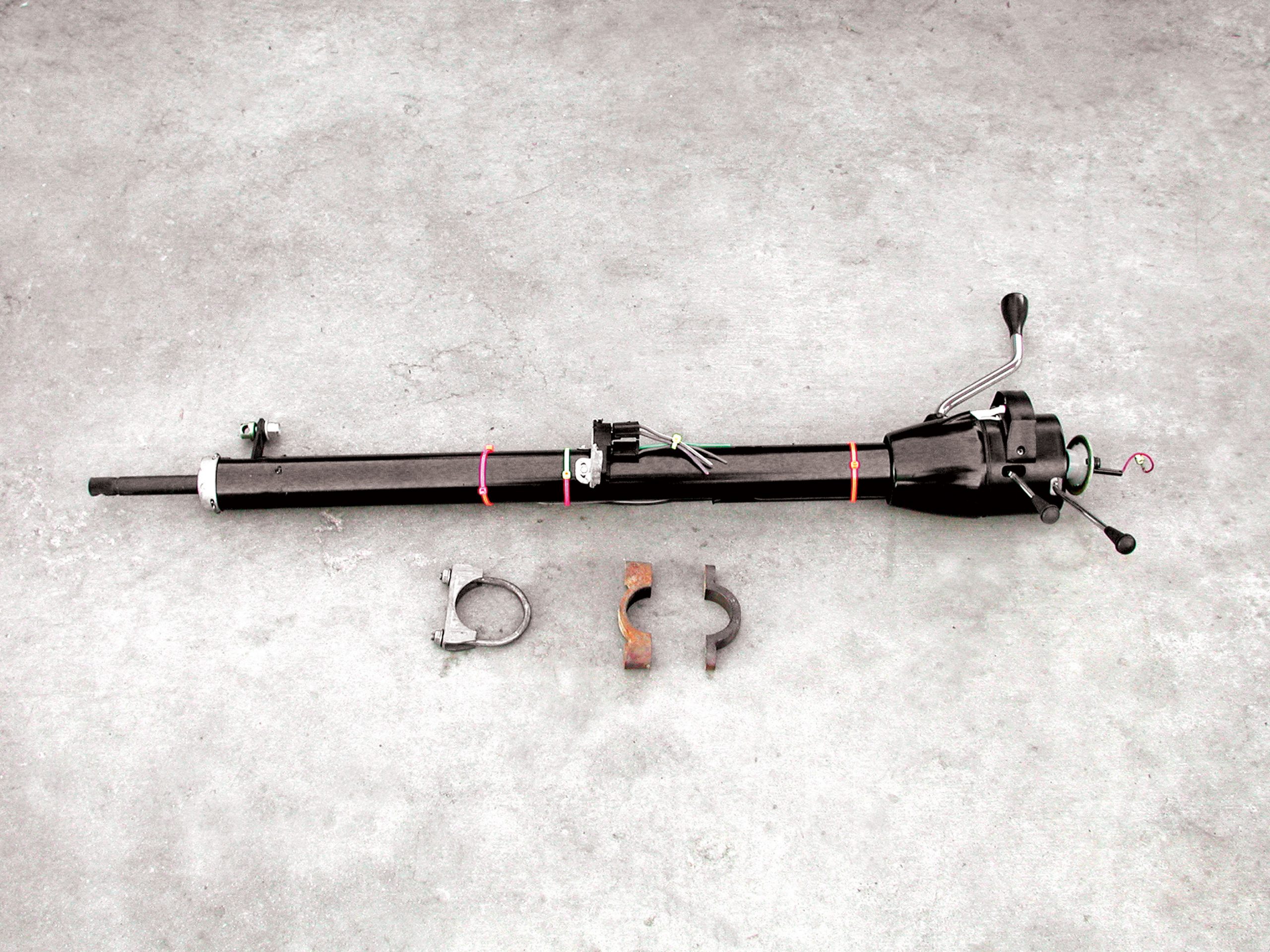

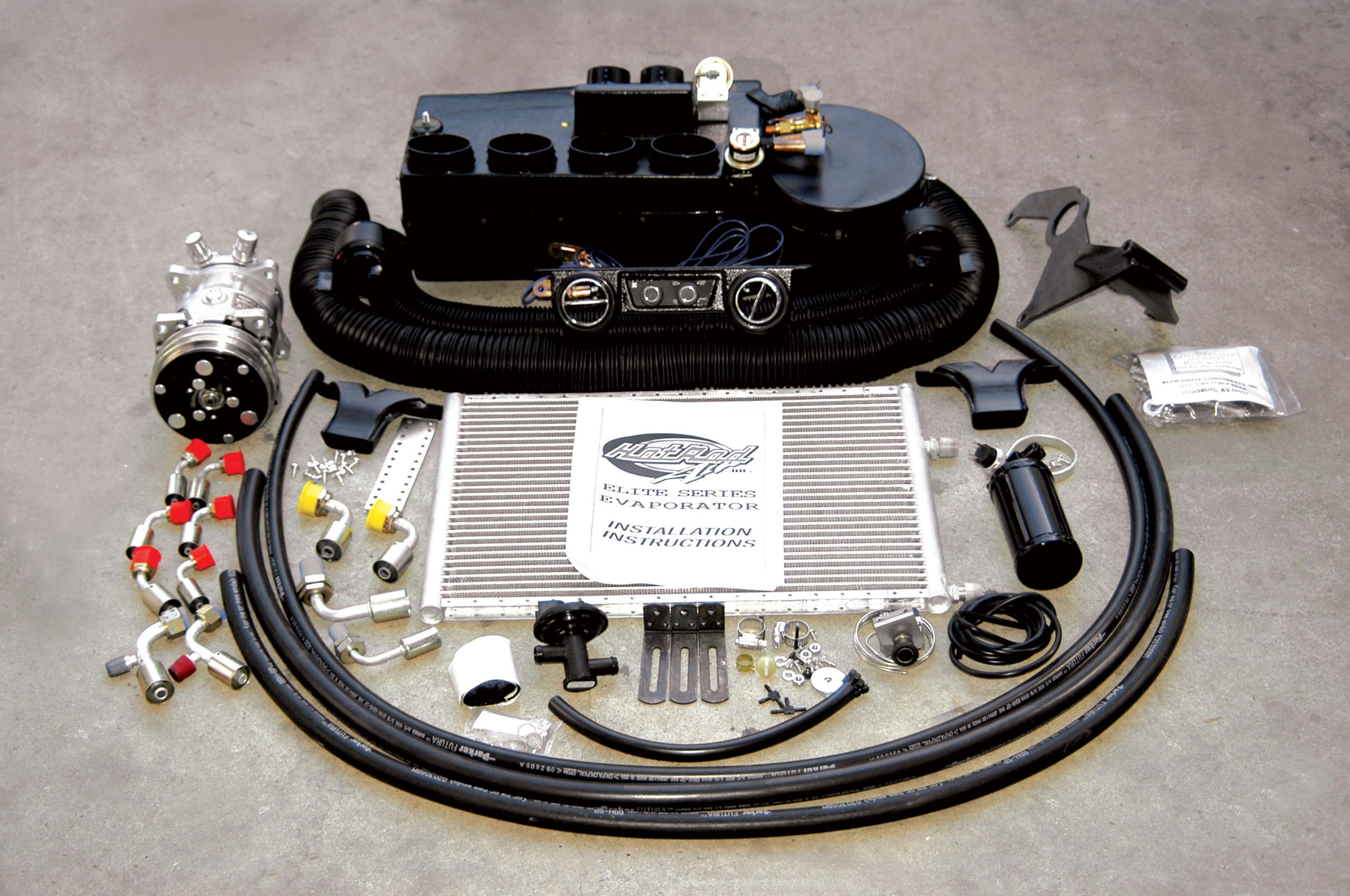

Most enthusiasts drive a newer car or truck for daily transportation, and we would dare say that most of them are equipped with power steering, power brakes and air conditioning. These are conveniences that most people take for granted and enthusiasts believe their street rods should have the same features.

Until the early ’70s, trucks were raw workhorses, and they rode high and hard. They were fundamentally designed to work hard. Overly simplistic suspensions were stiff but built to last. These trucks hauled loads around the farm and into town, carried work materials to jobs and even home goods and foodstuffs, much like the wagons of old. They performed their jobs well and for a long time.

Producing horsepower requires two major ingredients, namely, air and fuel. Of course, the two must be supplied in the correct proportions and at the proper time; but improving power is a simple matter of adding airflow. Naturally, additional fuel will be required once the airflow is improved, but the first item on the horsepower priority list should always be more airflow.

Smart boat owners know that diesel-powered towing vehicles are wise investments. A diesel powerplant’s premium price is eventually recovered through better fuel economy and engine longevity, and nothing quite compares to the off-the-line towing pull provided by a late-model oil-burner.

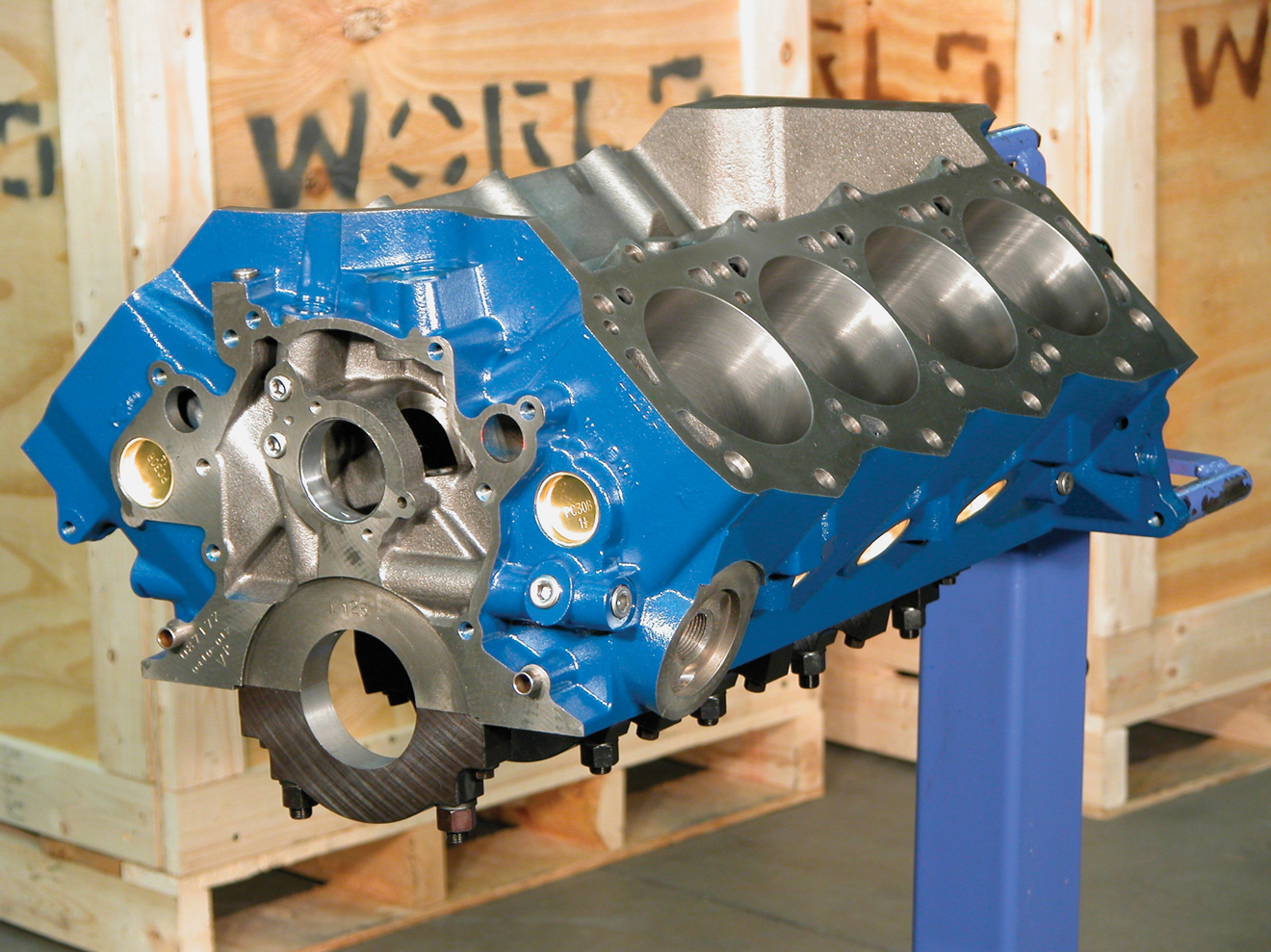

While the small-block Chevy is the popular engine choice for many enthusiasts, many are now relying on a Blue Oval heart for their performance bodies. With its link to Ford, the original body manufacturer for many of the classic cars we see today, the small-block Windsor-style Ford engine offers several advantages. When compared to Chevy, the lack of firewall clearance for a number of Chevy engine swaps is due to the rear distributor position of the engine. The front-mount distributor position is the more logical place to drive the distributor and the oil pump. Not to mention, it’s much more convenient.

One of the most misunderstood performance components on any engine has to be the camshaft, or camshafts in the case of our overhead-cam 4.6-liter Ford engine. The difficulty is only compounded when you add forced induction to the mix. From an anatomical standpoint, the camshaft can be likened to the brain, as the cam profile determines how effectively (when and where) breathing takes place.